When “REST” is a four letter word.

There she was again. Every single time I drove to the marina or over by the lake she was out running with her poodle. And I never went at the same time or kept a schedule.

Coincidence? Nope. She suffers from anorexia and exercise addiction.

If ever you’ve been a member of a gym for any stretch of time, you’ve likely witnessed those who just always seem to be there, no matter the time of day or day of the week you manage to slip in a spin class. Since I struggled with this in my past too, it was obvious to me before I set eyes on them. I knew their cars in the parking lot. And I could recognize their bags in the locker rooms.

But even a newbie exercise addict at the gym has “something about them”. No, the women don’t emit purple sparkly dust, and the men with an exercise addiction don’t all wear orange shoes. But IYKYK. (Mom, this means “If you know, you know.”)

Technically I don’t know if I agree 100% with calling this kind of obsession an addiction. I wrote a bit about this subject in my post titled “A prison that opens from the inside”. But for the susceptible person, the compulsive nature with which he or she caters to their cravings for physical activity shares a lot in common with addictions. As such, I’ll go ahead and use the term because, despite the nuances, it paints a fairly accurate picture of the associated telltale mechanistic behaviors and thought patterns.

If I could describe exercise addiction in one phrase, it would be: “REST is a four letter word.” REST could be replaced or closely followed by other expletives including HELP (as in getting it), CALM, and STOP. For me, YOGA qualified as well.

Needing HELP -> SHIT, especially if it’s an injury.

Being CALM -> bunch of CRAP.

STOP -> DAMN, I’ll do more tomorrow.

YOGA -> what the FUCK?

REST -> HELL no.

(Told you not to read this, Mom.)

Usually addictions are to substances or activities not supported by society whatsoever, and generally regarded as pretty bad. Exercise doesn’t fall into this category. Since the fitness boom of the 1970’s, much has been published on the benefits of physical exercise- and with good reason, given the countless psychological, physiological, and social benefits of physical activity.

But for an estimated 3% of adults in the United States, exercise goes too far, and crosses the line from healthy activity to addiction. That number increases dramatically when any form of training or sport is involved, or other addictions exist.

Risk factors for exercise addiction:

Certain factors can put a person at a higher risk of compulsive exercise. It is more commonly seen in people who exhibit certain personality traits, such as perfectionism, low self-esteem, neuroticism and narcissism, and those struggling with OCD.

Furthermore, having an addictive personality that also seeks satisfaction from other addictive substances or activities can increase the risk of exercise addiction even more. Researchers at the University of Southern California speculate that 15 percent of exercise addicts are also addicted to cigarettes, alcohol, or illicit drugs. An estimated 25 percent may have other addictions, such as a sex or shopping addiction.

Difficulty dealing with stress or negative emotions may also increase an individual’s risk. Pressure from society to have a perfect body may push someone to exercise compulsively to achieve an unrealistic ideal. These last two combined feed the incredibly high overlap between disordered eating and compulsive exercise. A body dysmorphic disorder, or body image disorder, may also lead to this end.

A shocking 39-48% of individuals suffering from an eating disorder or disordered eating engage in compulsive exercise.

Beyond internal struggles, external factors can also play a role. People in sports (and athletes in general) tend to have a higher risk of exercise addiction. Current research reveals that competitive athletes and gym-goers are at a much higher risk of developing exercise addiction:

Runners: 25%

Marathon runners: 50%

Triathletes: 52%

Endurance athletes: 14.2%

Fitness center attendees: 8.2%

What is it about exercise?

Exercise releases endorphins and dopamine. Most of us feel reward and joy when exercising. But for those who don’t make enough of these neurotransmitters, or whose “feel good” chemicals are in short supply due to stress, anxiety, or physiologic imbalances (ironically including nutritional), replenishing the pool through intense activity can provide an exhilarating “high”. Shortly after the exercise stops, the neurotransmitters go away. The individual then has to exercise more to trigger the chemical release again and try to stay in the positive state.

The general consensus is that an underlying difficulty in the reward processing center of the brain, which is responsible for keeping our neurotransmitters regulated, may exist in those who display impulsive and compulsive exercise behaviors. It becomes a way of self-medicating.

How do you know if this is you?

For starters, you probably have an inkling already. I know I did. It didn’t matter that I knew something was wrong, though, because I felt better doing it. And that’s all that matters, right?

Um, yes… until REALLY no.

Too much of any good thing is bad. To much exercise from an addiction? REALLY really bad.

But it is difficult, for the bystander as well as the runner, to know when working out to stay fit and enjoyment tips over into overload and takes on the dependency, tolerance, and withdrawal characteristics of an addiction.

Though multiple studies have been conducted, and numerous “diagnosis” criteria established to differentiate the two, subjectivity and individual self-awareness influences often skew results. But, as with degrees of disorder when it comes to food relationships, even the most sophisticated analysis cannot accurately measure the extent of physiological and psychological damage occurring. It’s up to the individual to recognize when their activity takes on a dark side, irrespective of the intention, duration, or intensity. Again, IYKYK.

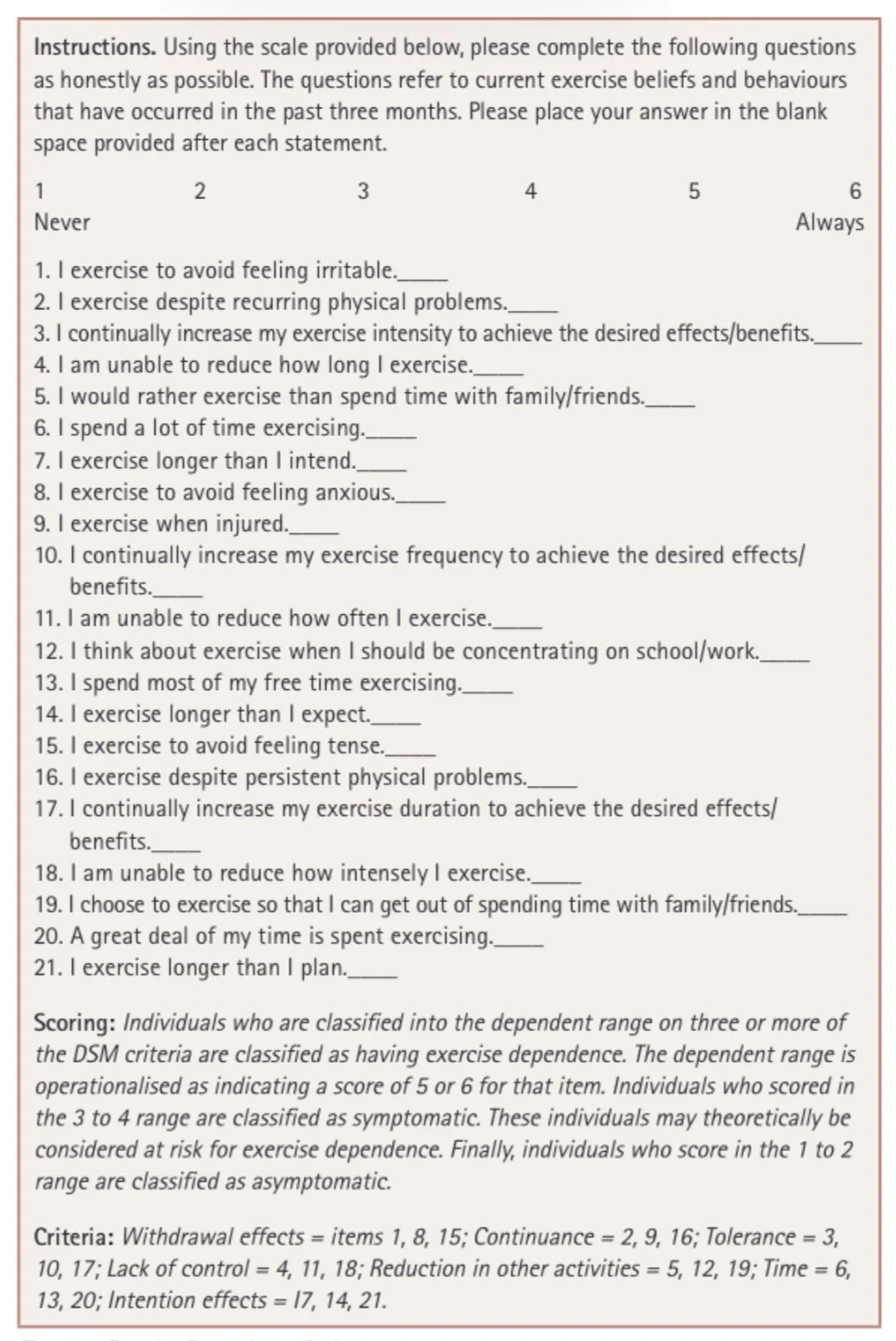

But for those of you who only have a suspicion, perhaps one you’ve zipped into the side pocket of your gym bag and locked away with a pink padlock coded for your birthday while you clock miles on a moving incline, below are seven standard criteria that indicate exercise addiction. If three or more of these resonate (be honest), step away from the machine… then sit your ass down for a month or six while you get your shit together in life. Cause this is eventually gonna kill what’s left of you.

Tolerance- Increased time spent or intensity is needed to achieve the desired effect (eg better mood, more energy).

Withdrawal- Negative emotional states such as anxiety, depression, distress, anger, or frustration occur if the exercise routine can’t be undertaken due to unforeseen circumstances such as weather, closings, or injury.

Intention- Despite planning to do only “x” amount of working out, it never seems to be enough, so the exerciser continues past this limit.

Loss of Control- Awareness that the extent of the physical activity is out of hand is not enough to change the behavior. Despite wanting to rest, spend time with others, eat food, or do other activities, more miles must be run… more step classes need to be attended. More weight needs to be pumped.

Time- An increasingly large part of the day is consumed by physical activity. Jobs may be sought after that allow for movement, vacations may be scheduled around hikes or recreation, and social groups joined often focus around group exercise. Time actually spent “resting” often includes reading or learning about exercise, training, and/or physical health.

Conflict- Engagements and activities that once brought pleasure may now be viewed as a problem if they impede on an exercise schedule or don’t involve enough movement.

Continuance- Pushing past pain, illness, or injury to complete a workout routine or training schedule are common occurrences.

Setting the immediate and ongoing harmful psychological consequences inherent to exercise addiction aside, there can also be devastating long term effects.

With the alarming association between chronic, obsessive exercise and dieting (or weight loss intention), relative energy deficiency syndrome (“REDS”) is a huge concern.

I spoke about homeostasis in my podcast titled “A perception of lack.” The body does its best to maintain health and balance, using what it’s given, and according to the stress load of its environment. But with energy deprivation, or expenditure above the level of available fuel, mere life comes at the expense of various “luxury” mechanisms in the body.

A person doesn’t need to look sick, or even lose weight, for the balance to be tipped in the favor of down-regulation and preservation. Push it further, and reproductive function, mental capacity, emotional resilience, bone strength, and vitality in every sense is lost.

To maintain the chemical “high”, and maintain the desired rate of weight loss or endurance, one most train longer and harder. The cycle continues. And it gets harder and harder to get off this treadmill of pain and dis-ease.

I’m not scripting these lines to frighten anyone. That would be a futile effort, given the grip strength of exercise compulsion. But, once enough of your life has been sucked into the gym vacuum and you don’t remember not aching or running in the rain, you may decide it’s time to face the giant who took control miles (or years) back. It’s worth considering these residual effects from the time abusing yourself mentally and physically, so you are aware of all that needs attention and repair.

I say “IYKYK” often enough when it comes to acknowledging exercise addiction, disordered eating, or that subtle awareness that you aren’t really steering the bike any longer. But I’m well aware that, depending on our social spheres, upbringing, media exposure, and lack of healthy role models in life, it’s not always readily apparent how we are struggling or what needs some attention and rebalancing. I spoke to this phenomenon in my article “Are you seeing clearly?”.

Below is a self-test from a research paper titled “How Much is Too Much? The Development and Validation of the Exercise Dependence Scale” using a rating system for the criteria discussed, to determine your individual level of exercise addiction risk.

If the notion of REST makes your skin crawl, the closest to YOGA breathing you care to approach is a running top with not quite enough support, or you collect stress fractures instead of stamps (or anything else more normal and less painful), but you don’t feel safe letting go, I’ll help you rip the bandaid off (or peal it off slowly if ongoing pain appeals). You may be surprised how good it feels to take a breather, and you’ll know you are finally taking care of yourself in an authentically healthy way. The gym will be there if healthy you decides you want to return one day, when you are actually free to make it a choice.